Author: Jordan DiNardo, Scripps Oceanography PhD Candidate & PIER Student – Summer 2019

The Program for Interdisciplinary Environmental Research (PIER) allows PhD students from nine interdisciplinary departments at UC San Diego to study at Scripps Institution of Oceanography and learn about the biological and societal challenges facing our oceans today. PIER students enroll in the MAS MBC Summer Course where they gain extensive science communication training alongside MAS MBC students. As part of our student blog series, we are excited to continue featuring students’ work from this past summer.

Gather round and cast your eyes on the marvelous butterfly of the sea before it’s too late! She’s one of a few of her kind. I present to you the Tiny, Talented Pteropoda (‘tera-poda’)! Watch as she flutters her wings and dances through the water column. This spectacle is quite special not only because she is a “flying” marine snail, but also because she is vanishing in our very oceans. Catch a glimpse of this spectacular creature while you still can!

Unlike their snail cousins who creep along the seafloor, pteropods use their muscular foot as wings to propel themselves through the water column. To sufficiently glide through water, a sea butterfly makes figure-eights with its wings and rotates its body back and forth. Its modified muscular foot, which helps to create a beautiful synchronized dance, gives the pteropod its name, which translates to “winged-foot” in Latin.

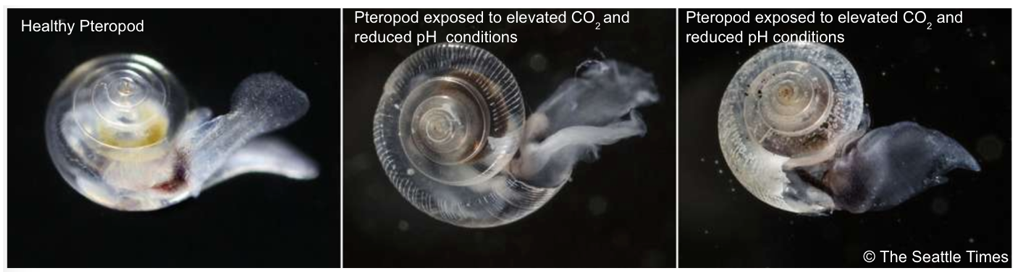

This tiny marine snail measures up to only 1/8 of an inch, which is about the size of a peppercorn. Despite their small size, pteropods are found in all major oceans at all latitudes, typically in the top 10 meters of the pelagic ocean. Pteropods’ delicate shells fall victim to elevated carbon dioxide (CO2) and decreased pH levels caused by ocean acidification.

Ocean acidification is the reduction in the pH of the ocean caused by the increased uptake of CO2 from the atmosphere. When CO2 is absorbed by our oceans, a series of chemical processes occur, resulting in an increased concentration of hydrogen ions. This increase in hydrogen ions causes the seawater to become more acidic (lower pH) and cause carbonate ions to be relatively less abundant. Unfortunately, these carbonate ions are important building blocks used by calcifying marine organisms to build their shells. The concentration of CO2 has increased through the past few decades due to the burning of fossil fuels. Like many marine organisms, pteropods are negatively impacted by this process.

Nina Bednarsek at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory in Seattle, was the first researcher to demonstrate biological impacts of ocean acidification, specifically on Pteropoda. In her study, Bednarsek looked at pteropods along the west coast of the U.S., ranging from Washington to California, and identified 50% of the sampled pteropods to have experienced severe damage to their shells. “It’s basically as if you poured acid on top of the shell or imagined burned skin of humans”, Bednarsek explained in an interview with KUOW Radio. With a quick look under the microscope, Bednarsek could easily see evidence of dissolution of the shells. In some of the areas in the Pacific Northwest, specifically along the Washington coast, where the pH is relatively lower (more acidic) all sampled pteropods revealed dissolved shells. These outcomes are only expected to worsen in the near future as pH continues to decrease.

The Tiny, Talented Pteropoda is vanishing from our oceans due to ocean acidification. If this process continues to worsen, the stunning butterfly of the sea may be nearing her last dance in our waters.